Debunking the Newark Anthropocentric Landscape

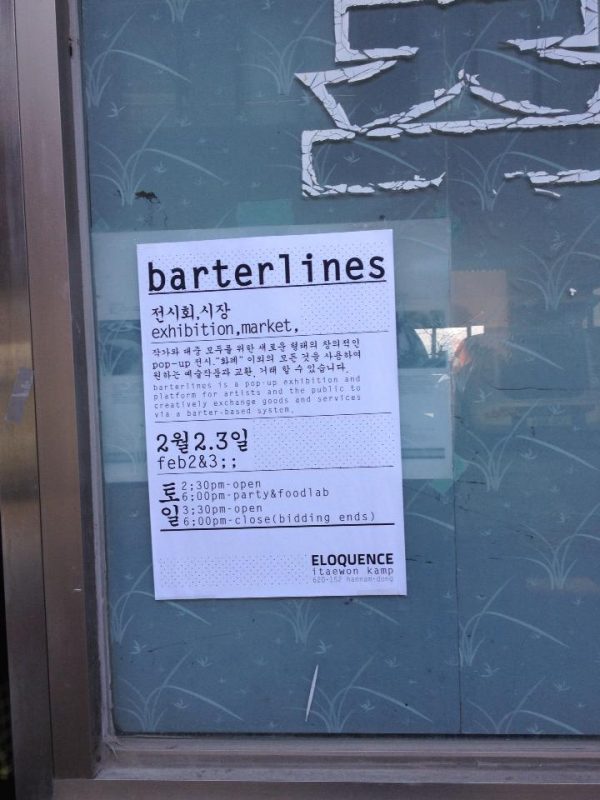

2011-2013 – Created love letter to Gangjeong Maul which was a raw documentary film of Korean karoke songs sung by activists fighting against the construction of a naval base to be built on a coastal lava rock that was home to an endangered crab species. Jamie Bruno served as an excellent distraction to police for the activists. She also created AMERICA THE GREAT which depicted the abstract relationship of national policy to the people it serves. She even created Barterline which allowed the public and many other artists to trade services and items with one another in the pop up exhibit.

2014-2015 – Began focusing on home bound compost policies with Planting Seeds of Hope and Urban Agriculture cooperative. She also worked to promote garden and educational focused policies with The Greater Newark Conservancy along with Foodcorp. She also created her own Free Weed exhibit which was a project of weeds stacked upon one another knocked down by random gallery visitors.

2016-2018 – Created a number of pro green communication projects with the Lower Raritan Watershed Partnership and finished a Printer-In-Residence specifically with the Newark Print Shop. She also created a variety of notebooks beautifully constructed from various recycled material known as River Walk as well as a functioning greenhouse which beautifully captures the struggle between vegetation and modern day urban elements. She also created Till It’s Gone, a set of square prints that captures the chaotic relationship between humans and the environment.

Soil health is indicative of our human health and social wellbeing. Anthropocentric interventions have transformed our soils in ways that have reduced quality of life for all animals, plants and humans. Newark-based artist, Jamie Bruno is leveraging soil’s importance, for larger cultural value. By converging soil with artistic practice, Jamie is fostering a new dialogue from which to view Newark not only as a place of confrontation but as a place of nourishment and sustenance. At the same time, Jamie communicates that our soil goes beyond the abiotic in that soil can become a platform from which we can enhance our own social relationships.

In an interview with My Central Jersey contributor, Bob Makin, Jamie Bruno discusses her desires to cultivate a reciprocal human-soil relationship with the local Newark community. “Dirt is a huge inspiration to me because, like water, its quality, condition, and history it tells stories about human nature, our origins, and our behavior…The built environment, due to our own ignorance or pride, works against natural systems and in turn, works against our own health and well-being. This has had a profound impact on me artistically and professionally and will be affecting my art-making and activism for many, many years into the future.”

Why is her work Meaningful for the Newark Community?

Environmental contamination as a result of industrial activity is omnipresent in New Jersey. The state has the highest number of superfund sites (113) as a result of underregulated industrial effluent discharge during the 20th Century. As said in an article titled “Dirty Little Secrets: New Jersey’s Poorest Live Surrounded by Contamination” published by WNYC News, For over a century, “New Jersey has been a hub for manufactured chemicals and products that became familiar fixtures in homes: charcoal and lighter fluid, plastic, guns, and silk. New Jersey’s history from the Industrial Revolution… generated toxic waste in a time of few if any environmental regulations.”

There are several sites in Newark worth noting: The Diamond Alkali Superfund site was a former Newark manufacturing facility for the chemical Agent Orange used in the Vietnam War. The White Chemical Corporation site used to be a facility that produced acid chlorides and flame retardants during the 1980s. Riverside Industrial Park site housed a range of industries from paint manufacturing companies, to chemical warehouses. In 2013 they were added to the Superfund Site List after an oil spill that leaked into the nearby Passaic River.

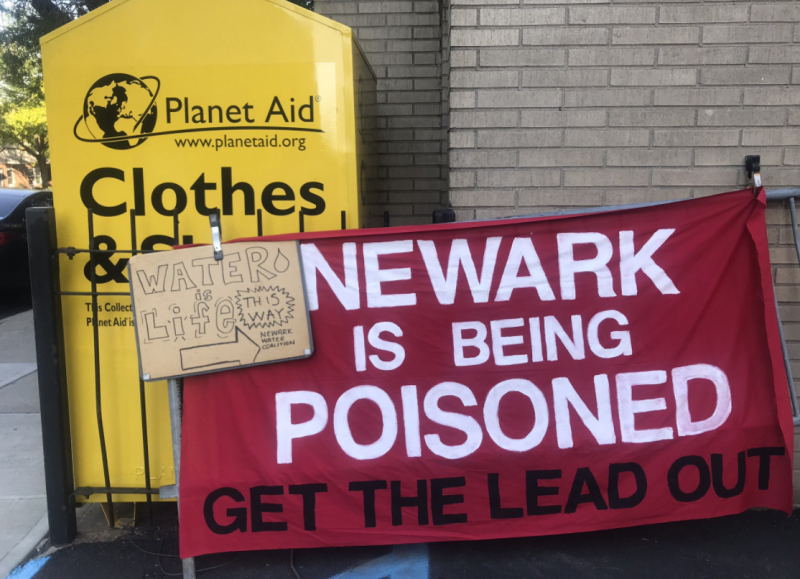

Newark also has a significant crisis when it comes to lead contamination. Newark had some of the highest levels of lead in drinking water in the United States. Lead contamination has a severe impact on kids from hyperactivity, slowed cognitive growth, hearing problems, and anemia. For adults, there’s cardiovascular effects, increased blood pressure and incidence of hypertension, decreased kidney function, and reproductive problems.

Jamie Bruno’s collaboration with Lower Raritan Watershed WADES Project is addressing water contamination as a result of soil degradation. Jamie Bruno describes “Here they make hand-casting molds while holding onto a piece of trash collected from the Raritan River… “My work is to bring people to the river and bring the river to the people. Increasing that knowledge and access increase people’s value of a healthy river and watershed.” The changes of the built environment placed upon the natural environment has prompted much of the social, economic, political problems that have stained our environmental history. While nature gives life to cities, it relies on an interdependency. If linear models of land-use and extraction prevail, then so will ecological disaster and disturbance. In all her pieces she communicates a radical rethinking of the human-nature relationship. As urban dwellers, we oftentimes forgot the importance of soil because we don’t have a physical daily connection to it. Jamie Bruno’s art is collaborative through projects like the WADES project. She wants her local Newark community, who may not have any physical connection to soil, to understand the importance of soil stewardship by actively being involved in her work. Advocating for soil protection through her art practice, she hopes to give the public and policy alike, visual tools to enact environmental change.

All Our Dead Can Live Again (2017)

All Our Dead Can Live Again is a functioning indoor greenhouse that uses worms to transform food wastes into soil, and serves to start seeds for gardens across Newark, New Jersey. The goal of the project was to have a mobile and impermanent space where local farmers could extend their growing season, and give them the opportunity to increase their annual yields.

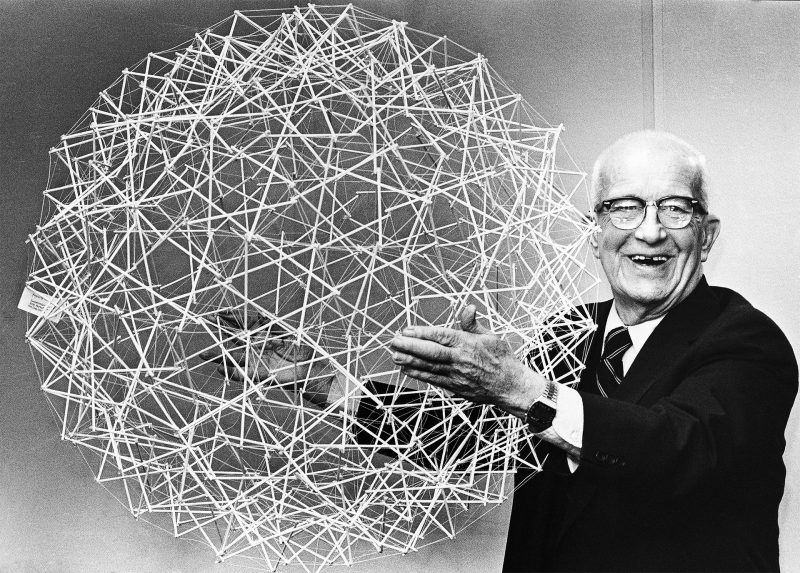

Her own inspiration for creating the dome was to bring attention to the relationship between the individual and the land. In the LANDHOLDINGS exhibition, the dome served as a way for attendees to escape the confines of the museum space, and enter into a world that highlighted the beauty and potential of urban agriculture.

Bruno’s All Our Dead Can Live Again is a 6 foot 3-inch dome, made up of inset triangles. It was first exhibited at the LANDHOLDINGS showcase at the Index Art Center in Newark, New Jersey. The showcase was curated by photographer Colleen Gutwein. The design for the greenhouse is inspired by the work of architect Buckminster Fuller, who was made famous by his geodesic dome structures.

The title for the project, “All Our Dead Can Live Again,” is a nod to the concept of regeneration, growth, and renewal in the industrial world. It acknowledges that the decay of our environment can be reversed, and although urban agriculture poses many issues and struggles, it also provides a glimmer of hope on the grounds of our future prosperity.

Till it’s Gone (2018)

18 square inch prints that combine drawing and photography. This forms a five-color bitmap screen process, forming with these prints which discuss human relationships with their environment. The drawings are simple by design, overlaying circular images mostly of either “nature” or anthropocentric forms (storm drains, refineries, gravel) with color alterations. This meshes together in a form which plays with objects in our lives and debates our relationship to them and nature. This was formed in 2018 under the Newark Print Shop’s residency program.

Work from this series also comments on the discussion of ephemerality and the context of natural versus built spaces. Works with larger connection to our natural environment evoke a deeper sense of connection and togetherness, while themes surrounding our built environment suggest segregation and consumption.

Evolutionary Work in New Jersey Composting

While working in the field of urban gardening and environmental protection, it seems that Jamie came to find composting and food waste a core issue facing our food systems today. Beginning with her work in 2014, Jamie acted as a co-founder and managing director at the start-up P3 Organic Exchange. P3 Organics was an environmental service company with the mission to “reduce organics in the waste stream and aid in regeneration of Newark’s communities from the ground up.” This work was where she found her groundings composting and is the beginning to her fight against restrictive regulations around the unused nutrients we simply throw away. Although the company ceased in 2016, Jamie had already made a name for herself in the urban agriculture world with a focus on composting that she still holds today.

It was this type of activist work that allowed her to speak at the 5th Annual Sustainable Living Empowerment Conference in 2017 where she hosted a round table discussing the stringent waste management regulations in New Jersey and how to become a compost advocate in one’s own neighborhood. She also gave talks on composting practices to a Rutgers cohort called “Annie’s Project NJ” where, as a keynote speaker, she discussed ways to compost and the state policy restrictions that much be critically evaluated for future urban agriculture health and efficiency.

In recent years, Jamie has co-founded the Urban Agriculture Cooperative (formerly known as Planting Seeds of Hope) with Emilio S. Panasci. At UAC, she has been working on a policy in New Jersey that will allow community gardens to accept small volumes of food waste in a legal and healthy fashion. On the UAC website, they state that, “composting completes the cycle of the urban food system, decomposing food waste down to new living soils that provide nutrients for plants, prevent erosion, absorb excess water, and store carbon.” This composting mission and other information can be found on their website, where the UAC has outlined the ways they are attempting to revert the composting narrative in New Jersey. The proposal given to the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection can be found here which outlines the reasons small holder urban gardens should allow for compost collecting when done in a safe manner that follows the EPA’a guidelines. Jamie and her fellow founders realized that there are people in the city who would like to compost their food but have no space to do so with limited areas and resources that accept it. This is especially true in New Jersey around low income areas where there are no yards for residences to compost properly. In addition to these roadblocks, further research uncovered that community gardens pose the same restrictions on “group compost collecting” as do “large scale waste facilities” as Jamie has cited. Realizing this, Jamie wrote to the local government and created a petition, formerly requesting that residence in these areas should be allowed to bring their compost to their local community gardens where it can then be put to good use rather than sent to the landfill. Connecting the needs of the community farmers that have to pay for expensive soil and local neighbors who throw away that same nutrients daily, is the kind of work that makes Jamie’s so compelling to follow. Not only is she creating stronger neighborly ties, but her “artwork” is socially constructive and can be seen as much more than art but a change in culture. Jamie’s request to the New Jersey Environmental Protection Agency (NJEP) was granted with the launching of a pilot program to “manage small volumes of food waste” which is still in the negotiation process with the hopes of launching soon. In an interview with the Rutgers and New York University classes, Jamie stated that “this pilot program is my baby” and she will be doing everything in her power to make sure it is successful. As she explains on her website “Local management of food waste is necessary for communities all over the state.”

Artist Jamie Bruno make this world more friendly step by step. Creating meaningful work that makes a difference, allows us to see the good in others and find hope, no matter how small or large that hope may be. Her work demonstrates the dream of finding one’s ‘niche’, an area that any artist hopes to find, where their passions collide with their values to create something bigger than themselves. Thanks to Jamie and her co-workers, less food waste will be going to the landfills in New Jersey and more mouths will be fed with nutritious and local food.

Barterlines (2013)

“As bleak as the current economic situation may be, there is a growing awareness that the cornerstone of any kind of alternative economy lies in empowering ourselves to image a different distribution of power and wealth.” (Erin Sickler 2012: Alternative Art Economies: A Primer. p. 250)

In 2013, Jamie Bruno collaborated with a group of artists on a group show called Barterlines in Itaewon, a neighborhood in the center of Seoul, South Korea. The distinguishing feature of this show was not just the art but specifically, the mode in which the art was valued and exchanged. The emphasis of the show was on imagining new ways for viewers to engage with and exchange art outside of the capitalist, art-market oriented norm. In her own words, Jamie Bruno said:

“What we did is we had artists submit essays on this relationship with money [and] their practice. We translated everything in Korean and English because we were in Seoul, in Itaewan, a small region in the center of Seoul. It was a bidding system, so we exhibited artists’ work, and people who came to the show would bid on the work. Some were joke bids, some were really great ones: personal itinerary, dentist, beer maker. It was just an interesting way to exchange artwork through barter. Of course I think that the conversation is a little different these days, definitely artists need to be paid for their time, and I think they’re often not paid for their time, but it was also that community cohesion between artists and other groups of people.” (Jamie Bruno, March 24, 2020)

Bruno also cites Alternative Art Economies: A Primer, which is a compilation of texts assembled by students at Trade School (“an alternative school where students offer goods and services in exchange for instruction,” Sickler, 242) in Manhattan, and the Institute for Wishful Thinking at Momenta Gallery in Brooklyn. The full article is part of a larger journal called Rethinking Marxism: A Journal of Economics, Culture, Society. It consists of “links, reading lists, and essays that relate to art’s economy” and was “assembled and discussed over the course of three workshops in spring 2011,” (Sickler, 242). The article focuses on barter as a way to diverge from the established modes of exchange.

While Barterlines engages directly with the idea of barter in the art economy, a byproduct is increased creativity on both sides of the exchange. In other words, in a system of negotiation and mutual agreement/aid, consumers are made to look within themselves to see what they can create and provide, along with the producers. As a result, there is a doubling of creativity and a proliferation of mutual support. For example, one viewer offered to “create a promo/profile video of you as well as some photos;” another: “10 sessions (45 minutes of session) of art therapy/counseling using art,” (Bruno, March 24, 2020). In effect, this creative economy doubles as a mutual aid network. Creativity and support are the currency.

While the primer focuses primarily on the artistic community and positions the artist as the deviser of these alternative systems, the effect of new, radical, sustainable, and socially-oriented economies could be far-reaching. Martha Rosler is cited in the primer. It reads, “Martha Rosler scrutinizes the ways that artists’ inclination to recognize beauty in blight has been instrumentalized for the purpose of real estate development,” (Sickler, 242). In other words, the artist has a certain ability to reimagine derelict spaces and, in some ways, instigate the process of gentrification (eventually inspiring the upper and middle classes to consider spaces in new ways). While this power may be more destructive than progressive in the case of real-estate development, the primer argues the power could be used to reimagine networks of exchange. It asks, “What then is to prevent artists from directing their efforts at devising communities based on cooperation and mutual aid?” (Sickler, 243).

The primer also situates food systems in relation to art economies: “…the food system is offered up as a proxy for the art world, as an industry that is currently testing the boundaries between luxury and necessity,” (Sickler, 242). This discussion of luxury and necessity is interesting. Perhaps it is because certain food producers and artists are accountable from the conception of their product to the distribution, that they are aware of the true cost and can therefore efficiently dictate price. While some products absorb costs of production, labor, capitalistic demands, and are influenced by speculative forces, the artist or the small business owner/farmer may be more in control of their own resources and therefore have autonomy in determining the price. When big corporations and or middlemen like galleries are eliminated, the exchange is short circuited, and is arguably more efficient and equitable for those involved.

This idea is imbued in Jamie Bruno’s other work as well. In her work with community gardens in New Jersey, she helps to build autonomy and control over local residents’ food sources and health. Both this effort and Barterlines, call on age-old practices to make space for exchange outside of capitalist norms. These small niches of mutual-support, care-based networks are conducive to sustainable art exchange, sustainable food exchange, and positive, environmentally-sound economies.

While Bruno has since focused on other projects, many alternative art-economies exist today. The primer provides a map of these networks in the continental United States. It defines these networks through the idea of critical regionalism, “a practice that responds to the local culture while simultaneously availing itself of an international aesthetic discourse,” citing also: horizontal governing structures, true democracy, volunteer labor, emphasis on “undervalued forms of labor, care, and collaboration,” (Sickler, 246).

In her talk, Bruno addresses how the conversations around economies like these are a bit different now. The emphasis, now, is more interested in ensuring artists are compensated fairly for their time. This is a valid and important argument. While it is definitely important to compensate artists justly and therefore in widely accepted ways, it remains important to continue to reimagine ways in which we exchange goods and services. Even as the free market economy continues to dominate, I believe injecting these networks of support, creativity, and care into cellular economies, when possible, could be beneficial and transformative.