Project Banaba is a exhibition by Banaban scholar and artist Katerina Teaiwa and curated by Samoan artist, Yuki Kihara. The exhibition is located in New Zealand, displaying the structured destruction of the Banaba island over the years from colonial forces.

Katerina Teaiwa is of Banaban, I-Kiribati and African American descent. Her groundwork focuses on the history behind imperial phosphate mining in Banaba, what is now the Republic of Kiribati. With the research she uncovered, her exhibition brings awareness to the immense and disastrous mining operations located in the island of Banaba, which resulted in forcing Banabans to relocate and develop strong survival mechanisms in the island of Rabi in Fiji.

Yuki Kihara is of Samoan and Japanese heritage. Her artistic work focuses on creating historical narratives connected with the postcolonial history throughout Oceania. These historical narratives are represented through different forms of art such as visual arts, dance, and curatorial tradition. Kihara also migrated to New Zealand in 1989 and has won many awards throughout her career, including the Creative New Zealand Innovation and Excellence Award, in 2009. Curating the exhibition of Project Banaba was significant because Kihara wanted to support in bringing awareness to the little-known mining history located in Banaba and the Banabans affected in the aftermath.

Banaba Island Origins

“Banaba was always rock, so even the sky was rock and the land falls from the sky into the ocean and becomes Banaba. The navel of the world, the place where everything is birthed from.”

Katerina Teaiwa

Image from National Archives ofhttps://www.anu.edu.au/news/all-news/banaba%E2%80%99s-history-of-exploitation-on-display

Banaban Man and Canoe in front of Canoe House, 1936. Photo courtesy of the National Archives of Australia, British Phosphate Commissioners

A new home in transit on the back of a truck in Tarawa.

Banaba, also known as the Republic of Kiribati, is a tiny coral island that has a region of only six square kilometers. This tiny island was once composed of organic and rich phosphates, and other natural resources. The island of Banaba was stripped away from their overflowing rich resources in the beginning of 1900. After being annexed by Britain, the operation of mining and shipping phosphate began and continued for eighty years. Through the eighty years of destruction, the indigenous people of Banaba were filled with empty promises and damaged agriculture. During World War II, the Japanese aimed to utilize Banaba’s phosphate resources, while reconstructing military guarding. Behind the functioning of military defenses, Banaban’s were forced to move into war camps and other areas of the Pacific. Following Japan’s defeat, the British provided Rabi Island to the survivors due to Banaba being in ruins and hazardous.

THE ROCK

“Phosphate was part of the green revolution. It allowed agriculture to expand globally and it also destroyed a lot of land and a lot of water resources.”

Katerina Teaiwa

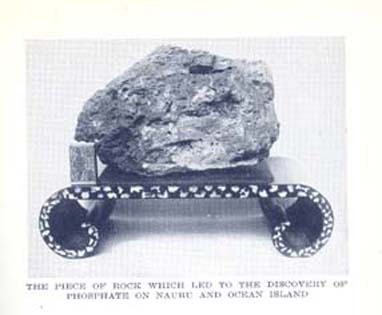

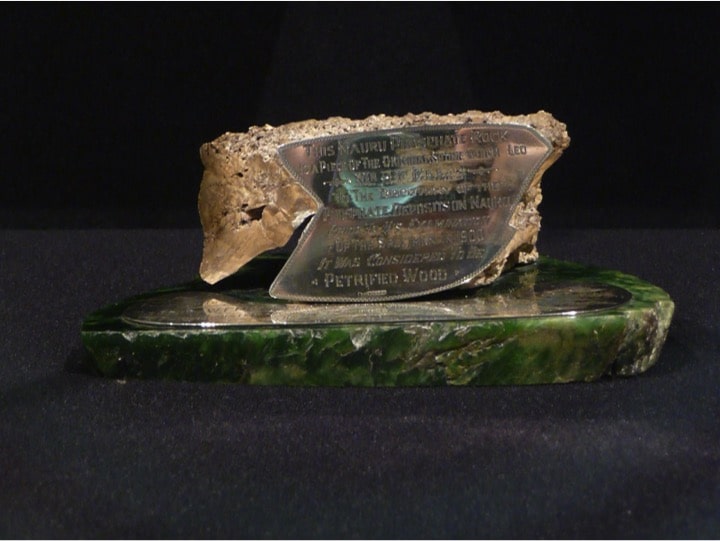

Phosphate was the rich, natural resource that captivated colonizers to intrude the island of Banaba. Phosphate was created from bird droppings, named guano. Guano is used as an essential fertilizer because it has high ingredients of nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium. The construction of phosphate minerals comes from guano and two islands, Banaba and Nauru, were heavily consumed with these bird droppings. The beneficial minerals of the rock was first recognized from a sample in a Sydney company office. Promptly after the invasion of explorers, a phosphate company was formed, known as the British Phosphate Commissioners. The British Phosphate Commissioners was controlled by Britain, Australia, and New Zealand. The minerals were assembled into superphosphate fertilizer and used to spread throughout farms across Australia and New Zealand.

While working in the company’s Sydney office in 1899, Sir Albert Fuller Ellis determined that a large rock from Nauru being used as a doorstop was rich in phosphate.

A piece of the phosphate rock doorstep (first mistaken as petrified wood) that led to the discovery of phosphate on Nauru and Banaba. Image by Nicholas Mortimer/Katerina Teaiwa

Destructive Mining

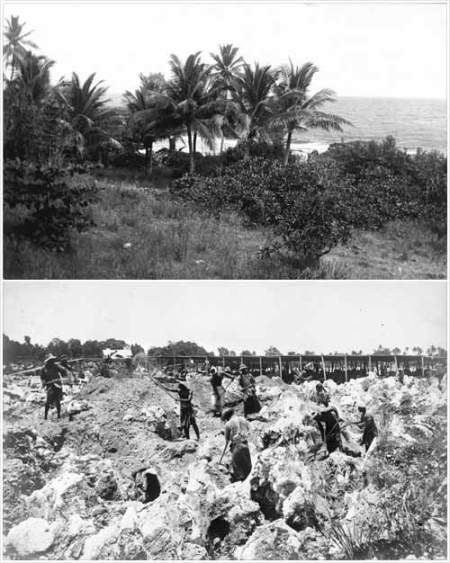

he first photograph shows the island shortly before mining began. The second was taken soon after, and shows how the vegetation and soil of Banaba were removed to extract the phosphate rock.

The serrated surface of the island of Banaba—the result of 80 years of mining. Photo credit: Janice Cantieri

“The landscape used to be 80 metres above sea level. And the (mining operators cut it down by 20 to 30 metres.”

Katerina Teaiwa

Beginning in 1900 and ending by 1980, phosphate rock mining stripped away 90 per cent of the island’s surface. After World War I, Banaba was positioned under the British Phosphate Commissioners- a board of Australian, British, and New Zealand representatives who controlled extraction of phosphate from next-door islands, Nauru and Christmas Island. The extraction of millions of tonnes of phosphate had reduced the island to a craggy jumble of coral; however it brought a great amount of agriculture to New Zealand and Australian agriculture. Phosphate was also transported to Japan. After the mining of phosphate, Banaba was left as a drought. There was barely any fresh water, and no surface streams.

A map of Banaba juxtaposed with the “Phosphate House,” which once stood on Collins Street in Melbourne. Next to it is an image of my hands holding a necklace with a pendant made from Banaban phosphate.

Phosphate mining infrastructure left on the island after mining stopped in 1980.

Injustice on Banaba

Arthur Grimble was a British civil servant and writer. He was known around Britain for the book he wrote titled, “A Pattern of Islands”, but to the Banabans, his method of speaking towards them made him seem condescending and cruel. He learned the Kiribati language in order to communicate with the residents on Banaba.

Grimble was sent by Britain during a summer of 1928 to persuade the Banabans to sell more land. However, by this time, the Banabans were done trying to offer up more land, much less 150 acres which is what the British demanded. One of the Banaban leaders, Rotan Tito, constantly challenged Grimble’s persuasion. Continuously, Rotan Tito asked for a certain amount of goods in exchange for the land that the British Phosphate Committee desired. Arthur Grimble’s response was,

“If you sign no land to the BPC, you are signing your own death warrant. Your people will die, you will be committing suicide”

Arthur Grimble

The Aftermath

As shown above, Banaba faces terrible issues currently due to the destruction caused by the British Phosphate Committee. However, an issue the island still continues to face today is the asbestos dust. Asbestos is a naturally occurring mineral which is found in metamorphic rocks, just like phosphate. Pure asbestos is extremely versatile, it can work with other materials to increase their durability. However, the issues and risks come with asbestos powder. When inhaled or ingested, the powder becomes forever trapped within the body. This is known as asbestos exposure and medical risks come from it. Over time, the trapped asbestos causes inflammation, scarring, and then eventually genetic damage to the body’s cells. A rare cancer, mesothelioma, is almost exclusively caused by asbestos exposure. Asbestos fibers cannot be seen, smelled, or tasted. It’s impossible to detect without taking the necessary precautions, which is why it’s dangerous.

Asbestos dust practically covers the floors of Banaban housing. It’s in fields, schoolyards, basically everywhere. There are broken pieces of asbestos sheeting that cover the ground and children use them to create toys.

“WE TRIED TAKING APART SOME OF THE ROOFING … AND WE BREATHED THE DUST—IT BURNED OUR LUNGS, OUR SKIN TURNED RED.”

Taboree Biremon

Reflection

Has any of your art been able to push you into an optimistic look into the future for Banaba and other spaces in the Pacific?

“The island is a live example of a ruin. People are actually living in it and with it. So, it’s optimistic because you know you can see the possibilities in what humans can do, living in an environment with no electricity, no running water, and no internet. It shows us human capacity for survival and for creative survival. Humans have a huge capacity to destroy the planet as we can see very clearly and they also have an amazing capacity to work with the environment to survive in all kinds of creative and interesting ways.”

Katerina Teaiwa