“I was also just really tired of the visuals that were being used to describe climate change. Aerial photography is important, but it allows people to dissociate from the scene if they don’t find something familiar or reflective of their own lives.

Virginia Hanusik

Who is Virginia Hanusik?

Love Desrosiers

Virginia Hanusik, a writer and photography artist, focuses on the correlation between the environment, landscape, and culture. Originally born in New York, Hanusik works with communities and state agencies in states such as Louisiana and New York. She is able to strategize climate adaptations, architecture, and environmental equity. After the constant shift and change of the Mississippi River, South Louisiana’s landscape has shifted as well. After all of the manufacturing that has occurred in the area, change is inevitable. As opposed to concentrating on scenes of flooding and debacle, this task investigates the effect of environmental change and adjustment in the area, and our relationship to these helpless spaces.

What are some of Hanusik’s most popular works?

Jessica Castillo & Margaret Berrios

A Receding Coast: The Architecture and Infrastructure of South Louisiana

In 2012, Texas Brine, a massive mining company operating throughout Texas and South Louisiana hit a salt dome that triggered the earth to be swallowed up. The Bayou Corne sinkhole in Assumption Parish, Louisiana, became a symbol of industrial greed at the expense of the natural environment. The adjacent community was forced to evacuate, most unable to return. While the media paid attention to the site immediately after, there’s been no continued documentation of what the physical landscape looks like and what it means in the larger context of climate change and social justice.

http://www.virginiahanusik.com/about-2

The Islands

As sea level rise threatens these liminal spaces, where land meets water, the landscape will undergo rapid change. In areas of Queens and Staten Island, managed retreat programs and high-premium flood insurance have moved residents away from the coast. In Manhattan and Brooklyn, luxury development projects bring the affluent to high-risk areas.

http://www.virginiahanusik.com/about-1

Bayou Corne

In 2012 a mining company hit a salt dome throughout Texas and South Louisiana that caused the earth to be swallowed up. Hanusik took these pictures below that captured the affect that it had on these landscapes.

“These photographs, taken between 2018 and 2019, are part of an ongoing project that explores the relationship between extraction, identity, memory, and its manifestation in the land. “

http://www.virginiahanusik.com/about-2

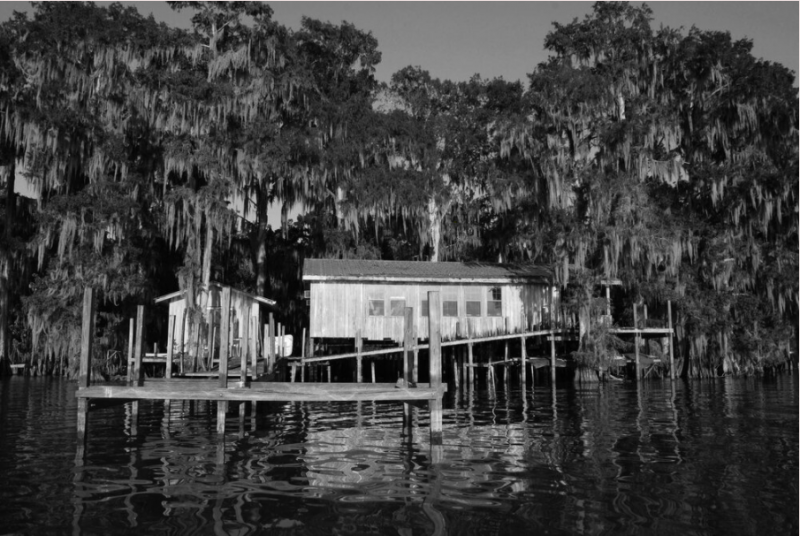

Hanusik mentions that her most significant work based on her hometown Louisiana. Below is a picture she has taken is called the Kees Family Camp on Lake Verret, which she considered her favorite place. The lake is over 14,000 acres long and is located in Assumption and Parish on Louisiana. To this day, it is now a location for fishing.

Hidden messages

As it is previously discussed what Virginia’s purpose behind her artwork, There are some hidden messages that can be found within her work. While looking at her works of landscapes becoming stranded because of water levels rising and environmental changes, hidden messages about mother nature can be taken from the scenery. The messages can be about nature losing its beauty because of the human race taking a lot for themselves and climate change continuing to rise as the weather becomes dramatically inconsistent and disrupts several biomes. What we can learn from her artwork and by figuring out some hidden messages from her work is to appreciate nature as nature is the root from where everything was created. We can also learn to appreciate mother nature for everything she has given us and to not take so much advantage of the fragile planet we call “home”.

What does beauty mean in the Anthropocene?

By Love Desrosiers

For something to be deemed “beautiful” it has to be aesthetic, especially to the eye. Ever heard of the saying “beauty is in the eye of the beholder”? Well, it simply implies that what one person may find aesthetically pleasing or admirable, another person may see differently. So, when I say “beauty” I am referring to the fascination of nature.

Hanusik has a gift for capturing true beauty in what everyone else deems to be trash or abandoned. Focusing on her project, “A Receding Coast: The Architecture and Infrastructure of South Louisiana”, many her photos are based in places where I naturally would call “horrifying” or even “horrid”.

However, the way she captures those places exposes that if you look at the right angle, you will see what the place is really worth. Someone once said, “when you stop expecting people to be perfect, you can like them for who they are”. This does not only apply to people, but it can also apply for Hanusik’s line of work, which is to simply inform others of the deteriorating nature of our environment. In order to move forward, we have to be able to look past the imperfections of the area. We must also be able to acknowledge all the imperfections and be willing to work with them. While on the outskirts of this area, people like me who do not necessarily have a story or connection to that area may not recognize its importance.

While attempting to find more about Virginia Hanusik and her work, I came across a man who goes by the name Emerson and he once said, “he should know that the landscape has beauty for his eye, because it expresses a thought which is to him good: and this, because of the same power which sees through his eyes, is seen in that spectacle”. Nature is said to be the wellspring of truth, goodness, and magnificence. This perspective on nature incorporates an intrinsic call to ensure what is valid, acceptable, and lovely. These are the things that we as people are looking for, are seeking out, but they’re directly before us if just we would tune in with our ear to the earth.

But many of us – those fortunate enough to have been spared from a terrible environmental disaster – don’t experience these events in the same way, or at least in a way that encourages lifestyle change

Virginia Hanusik

Emerson composes that “the perception of the inexhaustibleness of nature is an immortal youth”, further revealing that we tend to focus on things that may not be important. What really is important is to keep on enjoying our prompt experience with nature. Let us keep on being speechless, similar to the youngster on the beach, or climbing up a tree. Let us clutch that experience, and battle for the condition that makes it conceivable, for our inner child and the children that come in the next generations.

The truth is, no single image can properly convey the complexities of such a massive environmental transition.

Virginia Hanusik

What does Hanusik’s work mean for residents of Louisiana in the context of the Anthropocene?

In her project, “A Receding Coast: The Architecture and Infrastructure of South Louisiana” (research for which was supported by the Graham Foundation for the Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts), photographer Virginia Hanusik examines “the history of building practices and development in South Louisiana, and our collective memory as a landscape transforms.” Her work aims to spark discourse around sea level rise, which affects the whole nation, if not the whole world, but is particularly urgent for residents of Louisiana (which I am) and has been for decades.

In her photo “Entrance to Grand Isle, Jefferson Parish, Louisiana,” we see a sign reading, “Jesus Christ Reigns Over Grand Isle.” But does he? We all have different belief systems; Jesus Christ is merely a metaphor for a higher power, a force greater than humans. Let’s call it a metaphor for nature. Our current epic’s name – “Anthropocene” – alone suggests this might not be true. Perhaps Louisianans have cause to feel abandoned. Perhaps Louisianans have cause to feel hopeless. Perhaps the sign is moot – though the photograph does reflect our faithful, resilient spirit.

In her article “Changing the Visual Narrative of Climate Change,” Hanusik writes that what “is missing from the conversation is how Louisiana fits into the larger international paradigm shift of how we inhabit coastal space and what that physically looks like.” However, when speaking with Louisiana residents, she found that the international paradigm was of little importance to them. Of more importance was there connection to the land. “Throughout my time photographing in coastal parishes, the part that resonates with me most when talking with people is the deep connection between land and identity.” I can vouch for this. When I first saw Hanusik’s work, I cried.

Many New Orleanians feel territorial and protective of the city. We don’t necessarily like for non-native artists to depict us. However, Hanusik’s work offers a new perspective – a necessary, “outer” perspective. She shows us what we have been too blind to see – that our land is disappearing. Oh, the irony. What she makes visible, might soon be invisible.

If our identity is tied to our land, what happens when the land disappears? Does our identity shrink as the land we stand on shrinks? Have we Louisianans developed coastal anorexia? We are known for our heavy food, known for our crawfish boils. How can we take so much from the land, put so much meat on our bones, and yet, geographically, starve? How much longer till New Orleans becomes its nickname, City of the Dead?

Hanusik’s photos shift the climate conversation from temperature to topography. Those of us from Louisiana are resilient to heat. We love heat. We swim in heat! In fact, we’re more concerned by the cold. Why do we suddenly have winters? Because we live in a hot, humid climate, the global warming narrative escapes us. But seeing water where there should be land grabs our attention.

Many of us have been traumatized by flooding before. Hurricane Katrina is a recent example. The name “anthropocene” suggests that we who love and are made by this land are responsible for its wounds and our own subsequent trauma. That might be too hard for us to bear. We who love this land so much might have the heart to admit our suicidal ways, our self-sabotage. That’s why Hanusik is a gift to our culture. Her anonymity, her absence of ties to the land, gives her an objective gaze. She can save us. She can try, anyway, to expose our ways with her camera. She can try to save us from ourselves.

Bella Florence