Mary Ting is a visual artist with over 25 years of exhibiting her work in New York City and internationally. Her work on memory, loss and nature has received awards from the New York Foundation for the Arts, Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, and the Gottlieb Foundation among others. Mary received her BFA from Parsons School of Design, a diploma from the Central Academy of Fine Art, Beijing, and a MFA from the Vermont College of Fine Arts. Mary teaches at John Jay College in the art department and the Sustainability and Environmental Justice Program, in addition to the Transart Institute MFA in Creative Practices, Berlin/NY.

❋

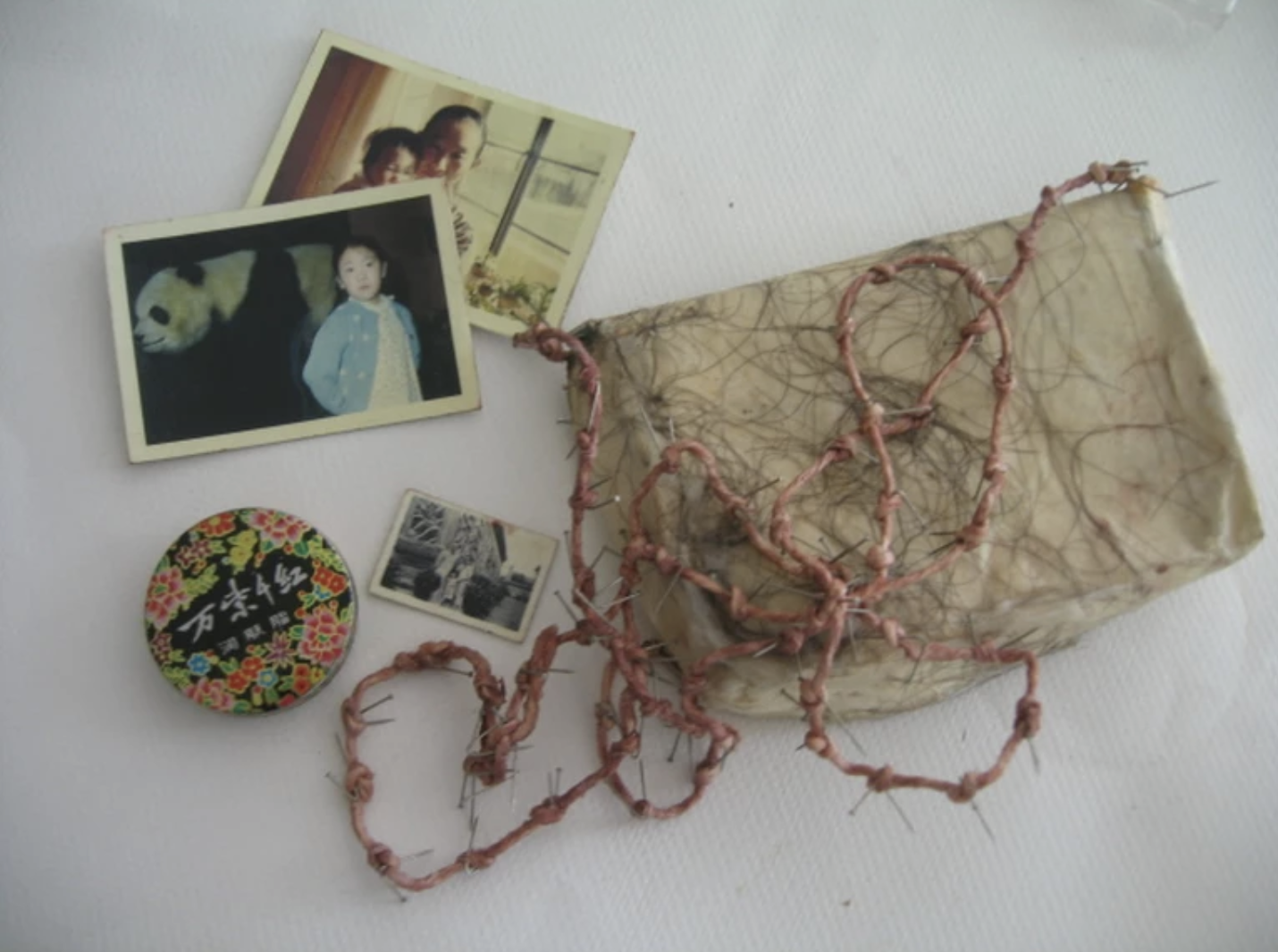

“I am Chinese-American visual artist working in a variety of formats from installations, sculptures, drawings, prints, to artist’s books. My work refers to memory, family and Chinese folk culture. Within my visual language of limbs, beaks, wounds, roots and Chinese symbols, lies a narrative. Psychological and sociological issues of isolation, endurance, and silence embody my forms. I view my pieces as visual poems; stories harsh and frightening but [ones] that are seldom told and lay deep within our bones. The work is personal, contemplative, and dark. It is the ‘memory collections, diaries of nightmares and sadness’ within us that interests and inspires me.”

Mary Ting, Artist Statement, [1999]

❋

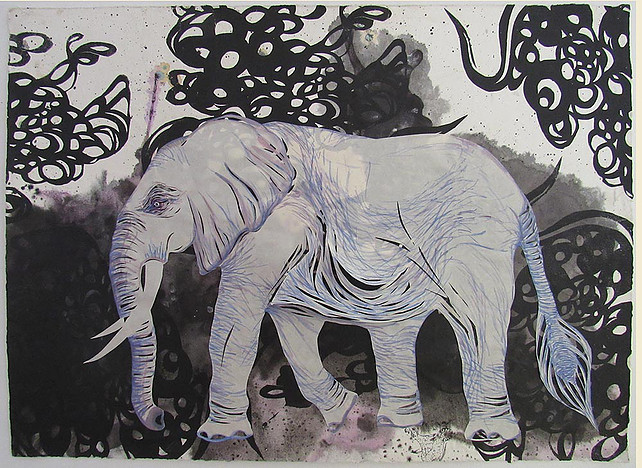

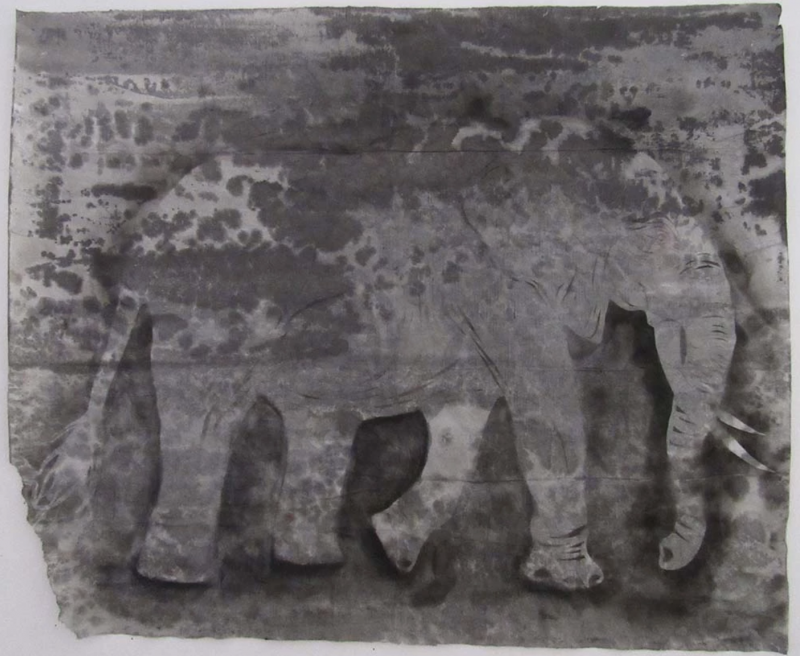

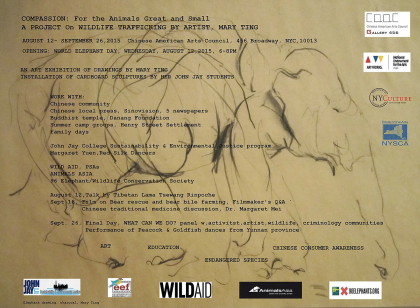

COMPASSION

For the Animals Great & Small

~Ongoing artworks revealing ironic tragedies behind wildlife products with the cultural and healthy facades~

///

At first glance of this artwork, one thinks of birds and death, because of Ting’s choice of using skeletal wings of birds and choice off bland dark color. According to Mary Ting the this art serves as a time portal trying to tell people a pece of her mother life story used for Ting bed night story, one day when her mother was at Nanjing college a little “American” boy whose father was a CEO of an oil company came into campus and was handed some sort of shooting weapon in which the child later used to shoot “nesting herons” around the area. In accordance with this Tings Mother felt the need to preserve the hopelessly shoot herons, and as a result of this

///

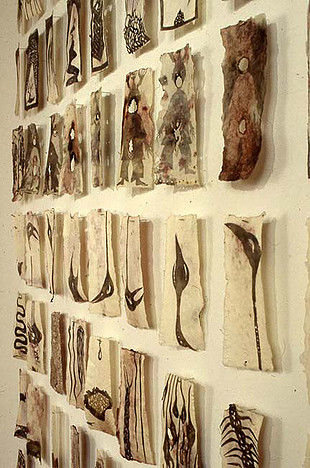

Shroud of Poison, Wave Hill, 2002-This piece demonstrates a technique Mary had learned from the women in the countryside of China that the artist has applied in some of her most recognized pieces. This is her take on the Shroud of Poison created with 300 paper cut out poisoned creatures at the bottom. The creatures included centipedes, snakes, spiders, scorpion, and toads. Each creature was cut out individually and covered in soot, which allowed people practicing this technique to create a stencil without re-drawing the figure over again. During this process, Mary would take one paper cut and lay it over a larger piece of paper and spritz it with water so that the paper sticks together, then lay it on a piece of wood or glass and flip the paper upside down. You would then take a candle and run it underneath it so that the candle is lighting through both pieces of paper so any place that there is a whole creates a stencil and once lifted off you would ultimately get two versions of the same design. This technique allowed the artist to create multiple stencils at a time, as well as creating a sense of darkness and fragility in the paper, in which the artist would often like to add into her work to create a sense of movement. Mary carries this technique in some of her most notable art works, such as Jinling Women’s University Memorial, Johnson State College, VT.

///

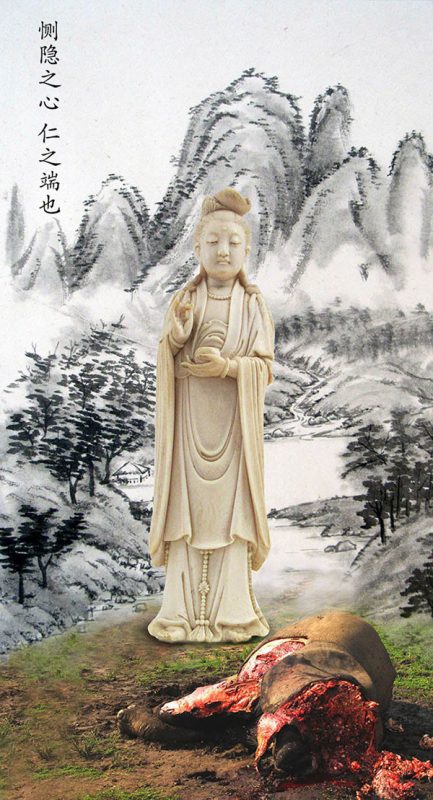

The Irony of the Ivory

This Guayana sculpture of the goddess of compassion made from ivory has played a significant role in Mary Ting’s childhood. She states that after her mother’s death and the Nanjing massacre the Buddhist sculpture always came up to her in mind. Additionally, Ting shares that her parents believed that the ivory used to make the sculpture “was picked up from the ground” coming from “elephant commentary”. It was then realized that the beautiful Guayana sculpture that was worshipped home is the result of the gruesome mutilation. Once Mary Thing was aware of this common atrocity, she developed a different outlook of what seemed so harmless. With great sorrow, she reveals, “the goddess of compassion who supposes to perceive and hear all cries for help is made out of a dead elephant, one that probably didn’t die from natural causes but was killed for its ivory”. The object’s presence is typical within a Chinese household due to their belief of “protecting and help for your family; however, what they don’t acknowledge is that immorality provided their tranquility. According to research, these ivory products have a high demand in the market with a value almost equivalent to diamond. Not only do these ivory products serve as a status symbol for Chinese families but around the world despite its dark origin.

///

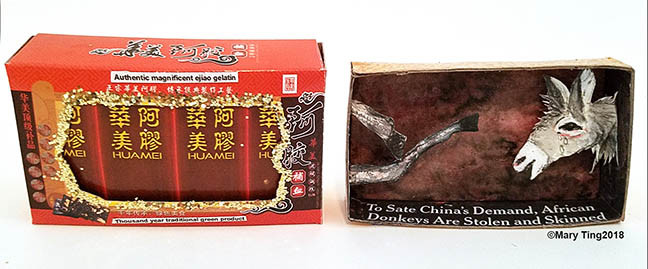

Tragedies Behind a Facade

“It is imperative to educate ourselves and our children, refuse to buy or consume these products and show our compassion for these animals by valuing their existence as living creatures. For me this is not merely an issue about animals, it is about caring about the world at large.“

What do you see?

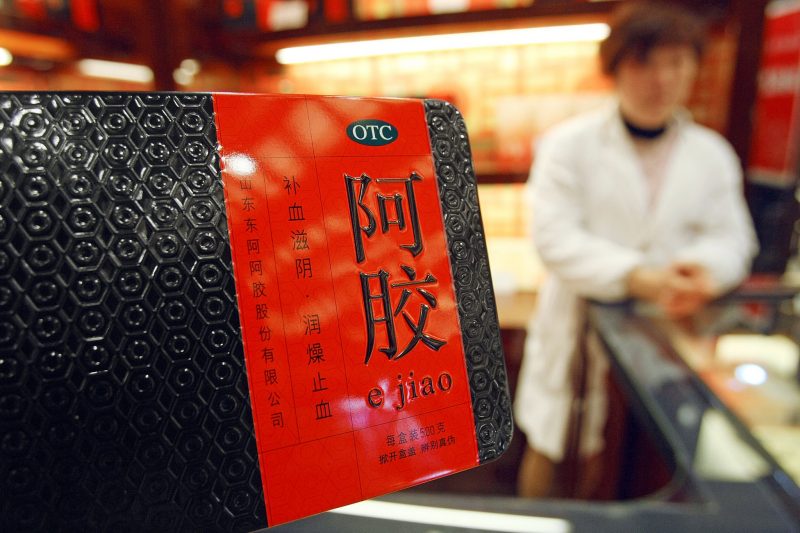

A simple red cardboard that holds a gelatin dessert? A product in which satisfy the appetite of an entire Chinese population? Look deeper into it. What the package fails to disclose with their consumers is that the gelatin, “Ejiao”, is made from donkey hides, prized as a traditional Chinese remedy. Ejiao was once prescribed primarily to supplement lost blood and balance yin and yang, but today it is sought for a range of ills, from delaying aging and increasing libido to treating side effects of chemotherapy and preventing infertility, miscarriage and menstrual irregularity in women. As demand increased, China’s donkey population — once the world’s largest — has fallen to fewer than six million from 11 million, and by some estimates possibly to as few as three million. In response to the current plight of animals endangered, Mary Ting chose the product above to encourage future consumers to start questioning the products they buy. How is this product made? What does the environment have to risk to fulfill my demands?